Bernard Tranel recently wrote to ask me if I “have come up with a satisfactory textbook for an undergraduate introduction-to-phonology course”. My reply was that I haven’t ever used a textbook for any introductory phonology course that I’ve taught; I always just use problem sets.

I know that many phonologists (and probably plenty of other types of linguists) use the same approach, but my particular inclination comes from having been an undergrad at UC Santa Cruz. Most if not all core linguistics courses were (and probably still are) taught without a textbook; the one exception that I recall clearly was — somewhat ironically — Phonology I, which I took from Armin Mester in the Winter of 1990. (By the way, Phonology I at UCSC was and still is numbered LING 101. Very appropriate, I think.)

Armin used Generative Phonology: Description and Theory (Kenstowicz & Kisseberth 1979). My memory of the class, though, is that we followed the text very loosely and mostly used it for the problem sets. (We may have been required to read a couple of the chapters, and I’m pretty sure I remember Armin using the Yokuts example in class, closely following the discussion in Chapter 4.) I got so into phonology at the time that I just read the whole book cover to cover, and it is still by far my favorite phonological theory textbook. I would maybe consider using it for an introductory course if I hadn’t already gotten so used to the flexibility and effectiveness of the problem-set-only approach.

In my humble opinion, no other text that is currently on the market — including Phonology in Generative Grammar (Kenstowicz 1994) — comes close to being as good as K&K’79. Each one that I’ve considered has been a major disappointment in one way or another and it would be very difficult for me to use any of them effectively in a class. I completely realize that my opinion is heavily influenced by the fact that K&K’79 was my first introduction to my chosen subfield; if someone has had a different first-hand experience than I have, either with K&K’79 or with another intro-to-phonology text, and either as a student or an instructor (or a writer!), please feel free to comment and/or post. (You should also feel free to comment and/or post if you share my opinion … I know there are at least two such people with user accounts on this blog — and y’all know who you are.)

I did notice (via LINGUIST List) that John T. Jensen has just published a textbook: Principles of Generative Phonology: An introduction. (I think it’s a little odd that this text is part of John Benjamins’ Current Issues in Linguistic Theory series, but in any event it’s a textbook and it’s out there.) I thought I’d take a look, so I ordered an examination copy and it arrived yesterday. During an afternoon lull I thumbed through it and realized just what it is that I like so much about K&K’79 and at least some of what it is that I don’t like about most — if not all — other texts.

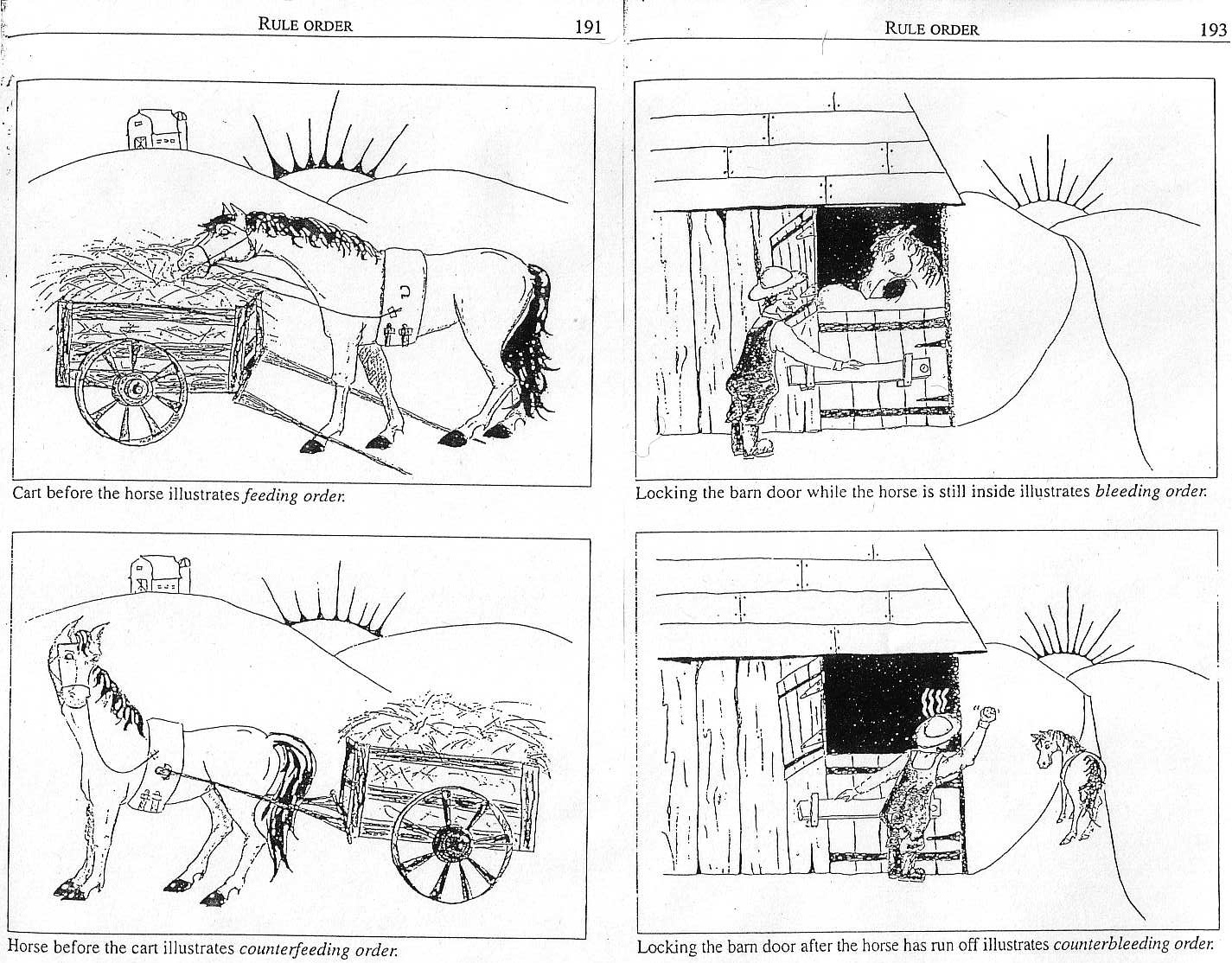

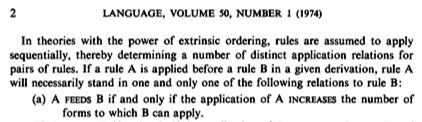

In Jensen’s chapter on rule order (Chapter 5), the same Yokuts problem set that is so effectively employed in K&K’79 is used to illustrate complex interactions among multiple rules. This is followed (pp. 189ff) by separate definitions and short discussions of specific rule interaction types. My first negative reaction was to the cartoons illustrating the differences between feeding and counterfeeding and between bleeding and counterbleeding. There’s really no good way to describe them; check them out for yourself:

I know firsthand that the distinctions among these rule interactions are not easy to learn, but these cartoons are more confusing to me than the concepts themselves. (I’m willing to believe that Jensen has field-tested these, but I still have my doubts.)

But worse are the mistakes that Jensen makes in the text discussion itself. Consider the following definition of feeding (p. 190 — I’ll get to footnote 14 in a little bit):

Assume that the grammar of a particular language has two rules, A and B, with A ordered before B. If, in a given derivation, the application of rule A creates a representation to which rule B can apply that was not present before the application of rule A, then rules A and B are in a feeding relation, or, equivalently, rule A is said to feed rule B.14

My two comments on this definition will at first seem like I’m being overly critical, but you’ll see that it’s quite deserved. First, consider a grammar with the following three rules, ordered as given:

Rule A: a → b / c __ d

Rule X: d → e / b __ f

Rule B: b → g / c __ d

Given the form /cad/, rule A feeds rule B. Application of rule A gives |cbd|, which allows application of rule B to give |cgd|. However, given the form /cadf/, rule A does not feed rule B. Application of rule A gives |cbdf|, which allows application of Rule X to give |cbef| — to which rule B cannot apply. (Rule X bleeds rule B in the second derivation.)

However, Jensen’s definition does not unambiguously state that Rule A does not feed Rule B in the second derivation. This is because of the ambiguity of the bolded words in this part of the definition: “the application of rule A creates a representation to which rule B can apply that was not present before the application of rule A”. Technically, rule B can apply to the output of rule A in the second derivation; it does not only because rule X crucially intervenes. So, can apply should be replaced with applies.

Second, it is technically not the case that the following two statements are equivalent, contrary to what Jensen’s definition states:

(1) Rules A and B are in a feeding relation.

(2) Rule A feeds rule B.

While it is true enough that (2) entails (1), (1) does not entail (2). (1) is also consistent with (3), but (2) and (3) are contradictory:

(3) Rule B feeds rule A.

I’m assuming, of course, that “equivalence” means “mutual entailment”.

OK, like I said, those two comments may seem overly critical, but I don’t think they are unfair criticisms for a textbook. Besides, consider Jensen’s footnote 14 — not only is Jensen overly (and unnecessarily) critical of two previous works, he is dead wrong about at least one of them.

An incorrect definition of feeding is sometimes encountered that ignores the relations within individual derivations and treats the concept in a kind of statistical fashion, for example (i), from Koutsoudas, Sanders, and Noll (1974, 2), who define the other relations in this section analogously.

(i) A feeds B if and only if the application of A increases the number of forms to which B can apply.

This definition is unable to account for rule relations that are feeding in some derivations and bleeding in others. It would, apparently, have to count the relevant derivations and declare the relationship to be feeding if there were more derivations in which it was feeding than those in which it was bleeding, an impractical and pointless exercise. This error is repeated in the recent textbook treatment of the subject (Gussenhoven & Jacobs 1998, 98ff).

I don’t have a copy of the Gussenhoven & Jacobs text — it’s one of those textbooks that I wasn’t thrilled with — but I do have a copy of the Koutsoudas et al. article (which I cited in a recent post). See for yourself: the relevant part of the relevant page looks exactly like this:

This snippet clarifies that Jensen’s “statistical” interpretation of Koutsoudas et al.’s definition is simply wrong — the phrase “in a given derivation” is right there on the page, loud and clear. And as if to prove that he thought that a quick re-reading of the relevant passage would also be “an impractical and pointless exercise”, Jensen later writes (p. 191):

It is important to note that terms like feeding and bleeding refer not to a pair of rules but to a pair of rules in a particular derivation (see footnote 14).

Does “particular” mean something completely different than “given” in the frame “in a _____ derivation”? I think not, and I’m sure Jensen would agree.

The most notable thing about K&K’79, I think, is the authors’ emphasis on argumentation, explicitness, and completeness. (This is also what made this text fit right into the UC Santa Cruz curriculum.) The way that the authors encourage these desirable analytical traits in the student is by engaging in them themselves. Sadly, this key element is lacking or at least underappreciated in many current texts. K&K’79 also neither condescends to nor expects too much from its audience — no oversimplified presentations, but no unnecessary citations every other sentence, either. It’s a textbook, but it’s also an excellent resource for the professional phonologist. I learn something new or recall something important almost every time I dig through it.

I do think that Kenstowicz & Kisseberth had a big advantage with their timing. By 1979, SPE had had a full decade to establish itself in the field; this was enough time for some very important questions about the theory to emerge and to be addressed in interesting ways. At the time (at least, in my necessarily retrospective view), Kenstowicz & Kisseberth were themselves in the thick of raising and addressing many of those important questions. And even though nonlinear alternatives were quickly establishing themselves at around that time, there didn’t seem to be a need to address those alternatives and I think it was a good thing that the authors didn’t. The problem now, of course, is that there’s so much more to address: linear vs. nonlinear, derivations vs. representations, rule ordering vs. constraint ranking … the list goes on. So it’s not like I think that writing a text as good as K&K’79 should be a walk in the park — but I’m still waiting to see one. Any suggestions?

(I am neither a student nor an instructor. I hope random amateurs are allowed to play.)

The first book on phonology I read was Jean-Louis Duchet’s _La Phonologie_, and I still love it dearly. It is rooted far more in (both) structuralist traditions and has only a little coverage of SPE generative theory (and none subsequent), so it couldn’t presumably couldn’t be used as a course.

Currently I’m reading Roca & Johnson, which is very generative indeed, and after the first hundred pages I don’t really have much pleasant to say about it. But it has already moved on from classical generative notation to autosegments of consonants before vowels have been discussed at all, and it takes the reader from no knowledge* to (allegedly) optimality theory.

*I think this is compulsory rather than permissible, but that’s perhaps not entirely fair. I don’t like it when people claim that the /p/~/b/ contrast in English is one of (straightforward phonetic) voice without at least admitting or hinting that it isn’t especially true, for example. Any wet-behind-the-ears newbie encountering this and Ladefoged’s phonetics books concurrently is going to wonder what’s up, and with more than just that.

As a former undergraduate student of John’s I’ll attest we never used cartoons in class. Back then I understood the ordering interactions, but not everyone in those classes did. Could be that presenting information in several different formats might reach more students. (But I hope there’s no such illustration for the Strict Cycle Condition).

I’m a former UCSC ( undergrad ) student, K&K is still on my bookshelf.

I haven’t had much experience with other phonology texts. The few that I’ve thumbed through since has seemed somewhat pedantic compared to our problem sets and K&K reference.

ps. found the blog recently thanks for jogging my phono-memories

When I began teaching in 1979, I was presented with written instructions about suitable textbooks. Schane’s (1973) Generative Phonology was recommended strongly. Hyman’s (1975) Phonology: Theory and Analysis was to be suggested to students who had studied phonology in the past and needed to review. Postal’s Aspects of Phonological Theory was “not a suitable textbook for this course”. K&K (1979) was just being published, so it wasn’t on the list.

Students who used the Hyman book for review, as recommended, thought it was great. I’m sure anyone would agree that Postal’s Aspects wouldn’t work as a textbook. I dutifully assigned Schane as the textbook, at least for undergrads, and was very happy with the results.

Schane’s book has several special characteristics. It’s really short — only xvi+127, according to our library’s catalog. It’s also very clearly written, so it was never necessary to spend class time explaining the textbook instead of explaining phonology. Schane uses the bare minimum amount of data, since the idea is to get the concepts across and not overwhelm students with the evidence. The most important thing, though, is that Schane has a chapter that describes and exemplifies each of the major types of phonological processes. For some reason, textbooks don’t often do that.

Another textbook I admire is Dell’s Les règles et les sons : introduction à la phonologie générative (apologies if the accented characters don’t come through). There’s a not very good 1980 English translation of parts of it. Dell’s book gives an excellent sense of the goals of the enterprise: why do we do phonology. He also presents very extensive examples that are worked through in great detail.

Pingback: phonoloblog » Counterpunch

Pingback: phonoloblog » X Counter{bl/f}eeds Y

Pingback: phonoloblog » Jensen text review

Pingback: phonoloblog » Should I be surprised?

Pingback: phonoloblog » More distributional arguments

Pingback: phonoloblog»Blog Archive » Still on the textbook trail

Pingback: phonoloblog»Blog Archive » Textbook review parallels

Pingback: phonoloblog»Blog Archive » Jensen text review

Pingback: phonoloblog»Blog Archive » Data and Theory: Papers in Phonology in Celebration of Charles W. Kisseberth

Pingback: phonoloblog»Blog Archive » Yuki & Yokuts